What Does Your Data Mean To You?

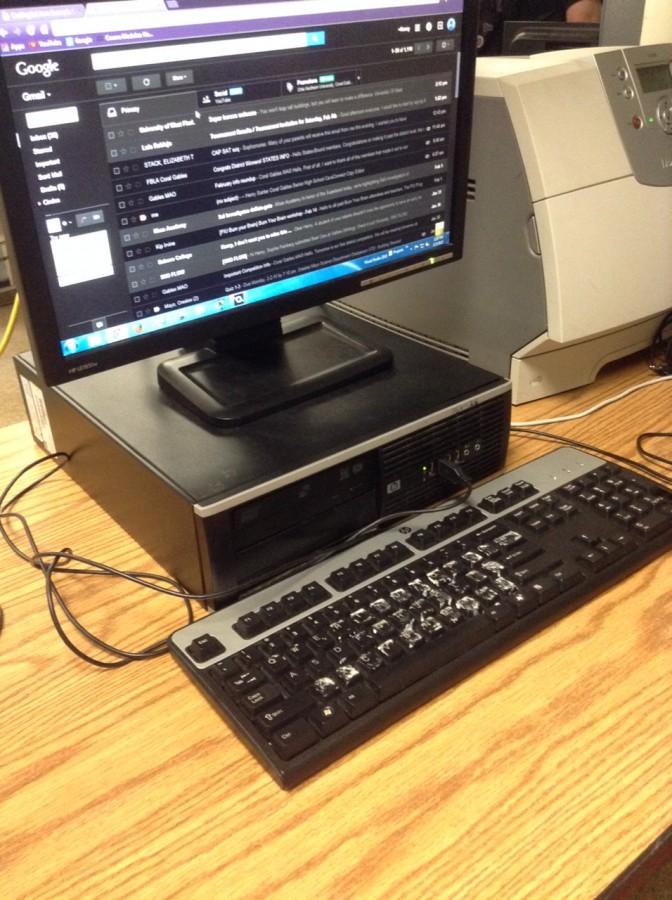

Though personal accounts are password protected with services such as Gmail and Outlook, they are still easily accessible to national security agencies that are interested.

Feb 15, 2015

The internet is incredible. It takes just seconds to be connected to your bank accounts, email accounts, social media accounts – everything. Almost all of the information that defines us is accessible online. And it is getting harder and harder to keep it safe.

Around the globe, governments are looking into new ways to break through the encryptions that are currently used on any data that get protected. In other words, they are getting better at invading our privacy; with each bit of progress they make, the chances that they can access encrypted messages and other information increase. Under the guise of increased national security, the right to privacy is being taken away from us – and we are only barely aware of it.

One of our most fundamental rights under the fourth amendment of the constitution is that of requiring a warrant before search and seizure of property. Is there any reason our digital property should be treated differently? Security agencies have just as much of a right to view our data without explanation as they do to break into our homes and go through our belongings unannounced.

There is some validity in using national security as grounds for needing to see what we do online. In light of the recent Charlie Hebdo incident in Paris, many officials are on high alert and are feeling the need to be particularly wary of online activity; having the ability to look into potential threats without worry about running into roadblocks such as PGP-encrypted messages can save a good deal of time in a situation where a difference of a few minutes can prevent an attack from taking place.

But how often do those situations come by? Terrorist attacks are not a dime a dozen; billions of violations of privacy on a regular basis do not have some definable value that needs to be exceeded for the payoff of preventing one to be beneficial. All that security agencies are doing is starting the same war on a new front – a virtual arms race, an unending cycle of new encryption, new code breaking method. And there is still no guarantee that the information they are accessing will not be used for other reasons, too.

“I think [government agencies collecting information without consent] is wrong, because the agencies are probably collecting data for other purposes – national security is just an excuse,” sophomore Javier Feliz said.

Privacy is both a right and a privilege; if it is to be taken away from people, it needs to be for more of a reason than preventative maintenance. It is simply not right for authorities to be able to learn anything they want about us without a more definite reason for it; by allowing it, we would be placing ourselves on a slippery slope that would only lead to further infringement.